CELTIC AND ROMAN TOWNS

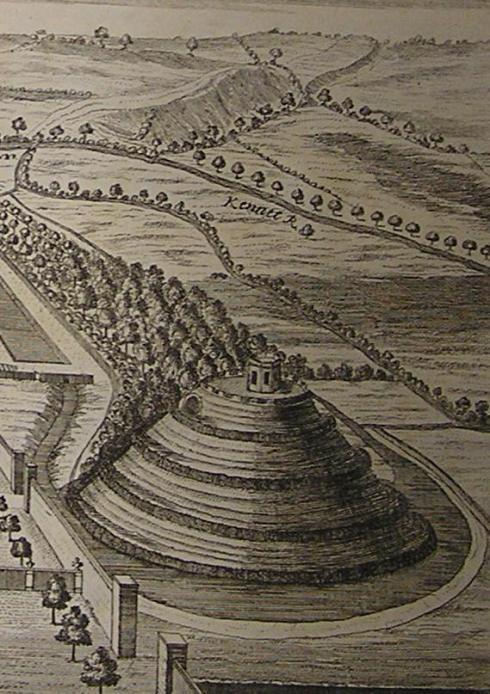

The Celts who lived in Britain before the Roman invasion of 43 AD could be said to have created the first towns. Celts in southern England lived in hill forts, which were quite large settlements. (Some probably had thousands of inhabitants). They were places of trade, where people bought and sold goods and also places were craftsmen worked. The Romans called them oppida.

However the Romans created the first settlements that were undoubtedly towns. Some Roman towns grew up near forts. The soldiers provided a market for the townspeople’s goods. Some were founded as settlements for retired legionaries. Some were founded on the sites of Celtic settlements.

However the Romans created the first settlements that were undoubtedly towns. Some Roman towns grew up near forts. The soldiers provided a market for the townspeople’s goods. Some were founded as settlements for retired legionaries. Some were founded on the sites of Celtic settlements.

Roman towns were usually laid out in a grid pattern. In the centre was the forum or market place. It was lined with public buildings.

Life in Roman towns was highly civilised with public baths and temples. At least some of the buildings were of stone with glazed windows. Rich people had wall paintings and mosaics.

However Roman towns would seem small to us. The largest town, London, may have had a population of only 35,000. The next largest town was probably Colchester with a population of around 12,000. Roman Cirencester may have had a population of 10,000. Most towns were smaller. Roman Chichester probably only had around 3,000 to 4,000 inhabitants.

Then in the 4th century Roman towns declined and in the 5th century town life broke down.

SAXON TOWNS

From the 5th century Angles, Saxons and Jutes invaded England. At first the invaders avoided living in towns. However as trade grew some towns grew up. London revived by the 7th century (although the Saxon town was, at first, outside the walls of the old Roman town). Southampton was founded at the end of the 7th century. Hereford was founded in the 8th century. Furthermore Ipswich grew up in the 8th century and York revived.

However towns were rare in Saxon England until the late 9th century. At that time Alfred the Great created a network of fortified settlements across his kingdom called burhs. In the event of a Danish attack men could gather in the local burh. However burhs were more than forts. They were also market towns.

Some burhs were started from scratch but many were created out of the ruins of old Roman towns. Places like Winchester rose, phoenix like, from the ashes of history.

TOWNS IN THE MIDDLE AGES

The thing that would strike us most about medieval towns would be their small size. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 London probably had a population of about 18,000. Winchester, the capital of England, probably had about 8,000 people. At that time a ‘large’ town, like Lincoln or Dublin had about 4,000 or 5,000 inhabitants and a ‘medium sized’ town, like Colchester had about 2,500 people. Many towns were much smaller.

However during the 12th and 13th centuries most towns grew much larger. (London may have had a population of around 45,000). Furthermore many new towns were created across Britain. Trade and commerce were increasing and there was a need for new towns. Some were created from existing villages but some were created from scratch. In those days you could create a town simply by starting a market. There were few shops so if you wished to buy or sell anything you had to go to a market. Once one was up and running craftsmen and merchants would come to live in the area and a town would grow.

In the Middle Ages most towns were given a charter by the king or the lord of the manor. It was a document granting the townspeople certain rights. Usually it made the town independent and gave the people the right to form their own local government.

In 1348-49 British towns were devastated by the Black Death. However most of them recovered and continued to prosper. Another danger in medieval towns was fire and many suffered in severe conflagrations.

ENGLISH TOWNS 1500-1800

In Tudor times towns remained small (although they were a vital part of the economy). The only exception was London. From a population of only about 60,000 or 70,000 at the end of the 15th century it grew to about 250,000 people by 1600. Other towns in Britain were much smaller. The next largest town was probably Bristol, with a population of only around 20,000 in 1600.

Nevertheless in the 16th century towns grew larger as trade and commerce grew. The rise in town’s populations was despite outbreaks of plague. It struck all the towns at intervals in the 16th and 17th century but seems to have died out after 1665. Each time it struck a significant part of the town’s population died but they were soon replaced by people from the countryside.

In the 18th century conditions in most towns improved (at least for the well off). Bodies of men called Improvement Commissioners or Paving Commissioners were formed with powers to pave, clean and light the streets (with oil lamps). Many towns also employed night watchmen. Most towns gained theatres and private libraries. However despite some improvements 18th century towns would seem dirty and crowded to us.

TOWNS IN THE 19TH CENTURY

From the late 18th century the industrial revolution transformed Britain. Many villages or small market towns rapidly grew into industrial cities. However, although most towns gained gas light in other ways conditions were appalling. They were dirty, overcrowded and unsanitary. Lack of building regulations meant poor peoples houses were often hovels. Not surprisingly British towns suffered outbreaks of cholera in 1832 and in 1848.

However in the late 19th century things improved. Most towns built sewers and created a clean water supply. New housing regulations meant that new houses were much better. Furthermore public parks and public libraries were created. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th most towns changed to electric street lighting.

At the end of the 19th century transport in towns was improved. From c.1880 horse drawn trams ran in the streets of many towns. At the beginning of the 20th century they were replaced by electric trams. In the 1930s most trams were replaced by trolley buses (buses that ran on overhead lines). However by the late 1950s most trolley buses had been replaced by motor buses.

Meanwhile a new kind of town had arisen – the seaside town. At the end of the 18th century spending time by the sea became fashionable with the wealthy. At first only they could afford it but from the mid-19th century trains made it easier for poorer people to reach the seaside. From the 1870s bank holidays (and for some skilled workers paid annual holidays) made the day at the seaside popular and many resorts boomed.

TOWNS IN THE 20TH CENTURY

At the beginning of the 20th century councils began the work of demolishing the dreadful 19th century slums. They also began building council houses. The work of slum clearance continued in the 1920s and 1930s. More council houses were built at that time. However most of the houses built in between the wars were private.

The 1920s and 1930s were difficult ones for northern towns as the traditional industries such as coal mining, ship building and textiles all declined. They suffered mass unemployment. However in the Midlands and the South some towns prospered with new industries such as electronics and car making.

During the Second World War many British towns suffered severely from German bombing. So many people were made homeless that after the war ‘prefab’ houses were built. They were made in sections in factories and could be assembled in a few days.

In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s slum clearance began anew. Vast swathes of old houses were demolished and replaced with council accommodation. Unfortunately much of it was in the form of high-rise flats, which suffered from social problems. In the late 20th century the emphasis changed from demolishing old houses to renovating them.

Furthermore following an act of 1946 new towns were built. Villages or small market towns were selected to take the ‘overflow’ populations of large cities like London. The new towns were greatly enlarged. New houses and factories were built to take the ‘immigrants’ from the big cities. It was the first time since the Middle Ages that large numbers of new towns were created. Among the new towns were Andover, Basingstoke, Crawley and Stevenage,

Meanwhile many town centres were ‘redeveloped’ in the 1960s and new shopping centres and car parks were built. Ironically at the same time increasingly strenuous efforts were made to protect old buildings.

In the late 20th century many northern towns suffered from the decline and even extinction of traditional manufacturing industries. However at the end of the century many managed to reinvent themselves and attract new service industries. In some towns trams were reintroduced.

British Tour Guide

HisTOURies UK The Best Tours in History

Read Full Post »

Archaeologists excavating the Weymouth Relief Road, on Ridgeway Hill near Weymouth, believe the pit of corpses comprises Iron Age war casualties massacred by the Roman Army.

Archaeologists excavating the Weymouth Relief Road, on Ridgeway Hill near Weymouth, believe the pit of corpses comprises Iron Age war casualties massacred by the Roman Army.

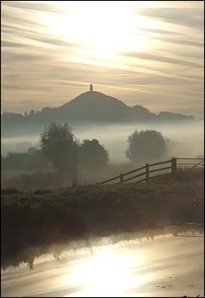

Legends of King Arthur swirl about Glastonbury like a tantalizing fog from the nearby Somerset marshes. The nearby hill fort at South Cadbury has long been suggested as the location for Camelot. Indeed, excavations of South Cadbury suggest that it was in use during the early 6th century, which is the likeliest era for the real Arthur to have lived.

Legends of King Arthur swirl about Glastonbury like a tantalizing fog from the nearby Somerset marshes. The nearby hill fort at South Cadbury has long been suggested as the location for Camelot. Indeed, excavations of South Cadbury suggest that it was in use during the early 6th century, which is the likeliest era for the real Arthur to have lived. Probably not. Legend holds that the earliest church here was founded by St. Joseph of Arimathea in about 60AD, and that when he planted his staff in the earth a thorn tree burst forth.

Probably not. Legend holds that the earliest church here was founded by St. Joseph of Arimathea in about 60AD, and that when he planted his staff in the earth a thorn tree burst forth.