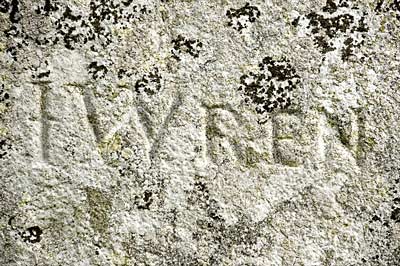

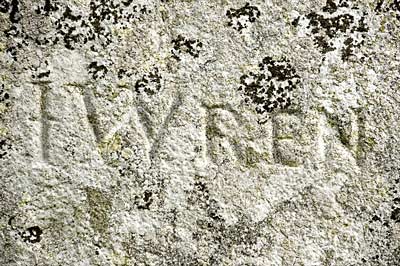

Sir Christopher Wren, the famous 17th century architect, left his mark on Stonehenge – but in a quite unexpected way. His name is skillfully chiselled into one of the 40-tonne sarsens that watches over the dig.

Christopher Wren Grafitti - Stonehenge

Was Christopher Wren a Mason ?

“Records of the Lodge Original, No. 1, now the Lodge of Antiquity No. 2”

mention him as being Master of the lodge.

Christopher WrenOne of the most distinguished architects of England was the son of Dr. Christopher Wren, Rector of East Knoyle in Wiltshire, and was born there October 20, 1632. He was entered as a Gentleman Commoner at Wadham College, Oxford, in his fourteenth year, being already distinguished for his mathematical knowledge. He has said to have invented, before this period, several astronomical and mathematical instruments. In 1645, he became a member of a scientific club connected with Gresham College, from which the Royal Society subsequently arose. In 1653, he was elected a Fellow of All Souls College, and had already become known to the learned men of Europe for his various inventions.

Christoher Wren

In 1657, he removed permanently to London, having been elected Professor of Astronomy at Gresham College. During the political disturbances which led to the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Commonwealth, Wren, devoted to the pursuits of philosophy, appears to have kept away from the contests of party. Soon after the restoration of Charles II, he was appointed Savillian Professor at Oxford, one of the highest distinctions which could then have been conferred on a scientific man. During this time he was distinguished for his numerous contributions to astronomy and mathematics, and invented many curious machines, and discovered many methods for facilitating the calculations of the celestial bodies. Wren was not professionally educated as an architect, but from his early youth had devoted much time to its theoretic study. In 1665 he went to Paris for the purpose of studying the public buildings in that city. and the various styles which they presented.

He was induced to make this visit, and to enter into these investigations, because, in 1660, he had been appointed by King Charles II one of a Commission to superintend the restoration of the Cathedral of Saint Paul’s, which had been much dilapidated during the times of the Commonwealth. But before the designs could be carried into execution, the great fire occurred which laid so great a part of London, including Saint Paul’s, in ashes.

Wren was appointed assistant in 1661 to Sir John Denham, the Surveyor-General, and directed his attention to the restoration of the burnt portion of the city. His plans were, unfortunately for the good of London, not adopted, and he confined his attention to the rebuilding of particular edifices. In 1667, he was appointed the successor of Denham as Surveyor General and Chief Architect.

In this capacity he erected a large number of churches, the Royal Exchange, Greenwich Observatory, and many other public edifices. But his crowning work, the masterpiece that has given him his largest reputation, is the Cathedral of Saint Paul’s, which was commenced in 1675 and finished in 1710. The original plan that was proposed by Wren was rejected through the ignorance of the authorities, and differed greatly from the one on which it has been constructed. Wren, however, superintended the erection as master of the work, and his tomb in the crypt of the Cathedral was appropriately inscribed with the words Si monumentum requiris, circumspice; that is, If you seek his monument, look around.

Wren was made a Knight in 1672, and in 1674 he married a daughter of Sir John Coghill. To a son by this marriage are we indebted for memoirs of the family of his father, published under the title of Parentalia.

After the death of his wife, he married a daughter off Viscount Fitzwilliam. In 1680, Wren was elected President of the Royal Society, and continued to a late period his labors on public edifices, building, among others, additions to Hampton Court and to Windsor Castle. After the death of Queen Anne, who was the last of his royal patrons, Wren was removed from his office of Surveyor-General, which he had held for a period of very nearly half a century. He passed the few remaining years of his life in serene retirement. He was found dead in his chair after dinner, on February 25, 1723, in the ninety-first year of his age.

Notwithstanding that much that has been said by Doctor Anderson and other writers of the eighteenth century, concerning Wren’s connection with Freemasonry, is without historical confirmation, there can, Doctor Mackey believed, be no doubt that he tools a deep interest in the Speculative as well as in the Operative Order.

The Rev. J. W. Laughlin, in a lecture on the life of Wren, delivered in 1857, before the inhabitants of Saint Andrew’s, Holborn, and briefly reported in the Freemasons Magazine, said that “Wren was for eighteen years a member of the old Lodge of Saint Paul’s, then held at the Goose and Gridiron, near the Cathedral, now the Lodge of Antiquity; and the records of that Lodge show that the maul and trowel used at the laying of the stone of Saint Paul’s, together with a pair of carved mahogany candlesticks, were presented by Wren, and are now in possession of that Lodge.” By the order of the Duke of Sussex, a plate was placed on the mallet or maul, which contained a statement of the fact.

C. W. King, who was not a Freemason, but has derived his statement from a source to which he does not refer (but which was perhaps Nicolai) makes, in his work on the Gnostics (page 176) the following statement, which is here quoted merely to show that the traditionary belief of Wren’s connection with Speculative Freemasonry is not  confined to the Craft. He says:

confined to the Craft. He says:

Another and a very important circumstance in this discussion must always be kept in view: our Freemasons (as at present organized in the form of a secret Society) derive their title from a mere accidental circumstances connected with their actual establishment. It was in the Common Hall of the London Gild of Freemasons (the trade) that their first meetings were held under Christopher Wren, president, in the time of the Commonwealth.

Their real object was political-the restoration of monarchy; hence the necessary exclusion of the public and the oaths of secrecy enjoined on the members. The presence of promoting architectures and the choice of the place where to hold their, meetings, suggested by the profession of their president, were no more than blinds to deceive the existing government.

Doctor Anderson, in the first edition of the Constitutions, makes but a slight reference to Wren, only calling him “the ingenious architect, Sir Christopher Wren.” Doctor Mackey was almost afraid that this passing notice of him who has been called “the Vitruvius of England” must be` attributed to servility. George I was the stupid monarch who removed Wren from his office of Surveyor-General, and it would not do to be too diffuse with praise of one who had been marked by the disfavor of the king. But in 1727 George I died, and in his second edition, published in 1738, Doctor Anderson gives to Wren all the Masonic honors to which he claims that he was entitled.

It is from what Anderson has said in that work, that the Masonic writers of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth, not requiring the records of authentic history, have drawn their views of the official relations of Siren to the Order. He first introduces Wren (page 101) as one of the Grand Wardens at the General Assembly held December 27, 1663, when the Earl of Saint Albans was Grand Master, and Sir John Denham, Deputy Grand Master. He says that in 1666 Wren was again a Grand Warden, under the Grand Mastership of the Earl of Rivers; but immediately afterward he calls him Deputy Wren, and continues to give him the title of Deputy Grand Master until 1685, when he says (page 106) that “the Lodges met, and elected Sir Christopher Wren Grand Master, who appointed Mr. Gabriel Cibber and Mr. Edmund Savage Grand Wardens; and while carrying on Saint Paul’s he annually met those Brethren who could attend him, to keep up good old usages.”

Brother Anderson (on page 107) makes the Duke of Richmond and Lennox Grand Master, and reduces Wren to the rank of a Deputy; but he says that in 1698 he was again chosen Grand Master, and as such “celebrated the Cape-stone” of Saint Paul’s in 1708. “Some few years after this,” he says, “Sir Christopher Wren neglected the office of Grand Master.” Finally he says (on page 109) that in 1716 “the Lodges in London finding themselves neglected by Sir Christopher Wren,” Freemasonry was revived under a new Grand Master. Some excuse for the aged architect’s neglect might have been found in the fact that he was then eighty-five years of age, and had been long removed from his public office of Surveyor-General. Brother Noorthouek is more considerate. Speaking of the placing of the last stone on the top of Saint Paul’s-which, notwithstanding the statement of Doctor Anderson, was done, not by Wren, but by his son-he says (Constitutions, page 204): The age and infirmities of the Grand Master, which prevented his attendance on this solemn occasion, confined him afterwards to great retirement; so that the Lodges suffered from many of his usual presence in visiting and regulating their meetings, and were reduced to a small number.

Brother Noorthouck, however, repeats substantially the statements of Doctor Anderson in reference to Wren’s Grand Mastership. How much of these statements can be authenticated by history is a question that must be decided only by more extensive investigations of documents not yet in possession of the Craft. Findel says in his History (page 127) that Doctor Anderson, having been commissioned in 1735 by the Grand Lodge to make a list of the ancient Patrons of the Freemasons, so as to afford something like a historical basis, “transformed the former Patrons into Grand Mastefs, and the Masters and Superintendents into Grand Wardens and the like, which were unknown until the year 1717.” Of this there can be no doubt; but there is other evidence that Wren was a Freemason. In Aubrey’s Natural History of Wiltshire (page 277) a manuscript in the library of the Royal Society, Halliwell finds and cites, in his Early History of Freemasonry in England (page 46) the following passage: This day, May the 15th, being Monday, 1691, after Rogation Sunday, is a great convention at Saint Paul’s Church of the Fraternity of the Accepted (the word Free was first written, then the pen drawn through it and the word Accepted written over it) Seasons, where Sir Christopher Wren is to be adopted a brothers and Sir Henry Goodrie of the Tower, and divers others. There have been Kings that have been of this sodality.

If this statement be true-and we have no reason to doubt it, from Aubrey’s general antiquarian accuracy-Doctor Anderson is incorrect in making him a Grand Master in 1685, six years before he was initiated as a Freemason. The true version of the story probably is this: Wren was a great architect-the greatest at the time in England. As such he received the appointment of Deputy Surveyor-General under Denham, and subsequently, on Ocnham’s death, of Surveyor-General. He thus became invested, by virtue of his office, with the duty of superintending the construction of public buildings.

The most important of these was Saint Paul’s Cathedral, the building of which he directed in person, and with so much energy that the parsimonious Duchess of Marlborough, when contrasting the charges of her own architect with the scant remuneration of Wren, observed that “he was content to be dragged up in a basket three or four times a week to the top of Saint Paul’s, and at great hazard, for £200 a year.”

All this brought him into close connection with the Gild of Freemasons, of which he naturally became the patron, and subsequently he was by initiation adopted into the modality Wren was, in fact, what the Medieval Masons called Magister Operis, or Master of the Work. Doctor James Anderson, writing for a purpose naturally transformed this title into that of Grand Master-an office supposed to be unknown until the year 1717. Aubrey’s authority, in Doctor Maelsey’s opinion, sufficiently establishes the fact that Wren has a Freemason, and the events of his life prove his attachment to the profession.

Whether Sir Christopher Wren was or not a member of the Fraternity has long been debated with lively interest. The foregoing statement by Doctor Mackey gives the principal facts and we may note that two newspapers announced his funeral, Lost boy (No. 5245, March 2-5, 1793) and the British Journal (No. 25, March 9, 1723).

Both of them allude to Wren as “that worthy Freemason.” Brother Christopher Wren, Jr., the son of Sir Christopher Wren, was Master of the famous Lodge of Antiquity in 1729. The subject is discussed in Doctor Mackey’s revised History of Freemason also by Sir John S. Cockburn, Masonic Record, March, 1923, in Square and Compass, September, 1923, and many other journals, as well as in Records of Antiquity Lodge, volume i, by Brother W. H. Rylands, and volume ii, by Captain C. W. Firebrace, there is much additional and valuable firsthand information favoring Wren’s active connection with the Fraternity, some items personally checked by us at the Lodge itself.

Brother K. R. H. Mackenzie in the Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia says,

There can be little doubt that Wren took a deep interest in speculative as well as operative Masonry (see Book of Constitutions) and that he was an eminent Member of the Craft cannot be doubted, but the dates respecting Wren’s initiation are vague and unsatisfactory, none of the authorities agreeing. It would seem certain, however, that for many years he was a member of the old Lodge of Saint Paul’s, meeting at the (Bose and gridiron, in Saint Paul’s Churchyard.

Brother Robert F. Gould (History of Freemasonry, me ii, page 55) says, The popular belief that Wren was a Freemason, though hitherto unchallenged, and supported by a great weight of authority, is, in my judgment, unsustained by any basis of well-attested fact. The admission of the great architect-at any period of his life-into the Masonic fraternity, seems to me a mere figment of the imagination, but it may at least he confidently asserted, that it cannot be proved to be a reality.

Rev. A. F. A. Woodford, Renning’s Cyclopedia of Freemasonry, says, In Freemasonry it has been general for many years to credit Sir Christopher Wren with every thing great and good before the ” Revival,” but on very slender evidence. He is said to have been a member of the Lodge of Antiquity for many years; “and the maul and trowel used at the laving of the stone of Saint Paul’s, with a pair of carved mahogany candlesticks, were presented ” by hind and are in the possession of the Lodge.

Doctor Anderson chronicles him as Grand Master in 16S5; but according to a manuscript of Aubrey’s in the Royal Society, he was not admitted a Brother Freemason until 1691. Unfortunately, the early records of the celebrated Lodge of-Antiquity have been lost or destroyed, so there is literally nothing certain as to Wren’s Masonic career, what little has been circulated is contradictory. It is, of course, more than likely he took an active part in Freemasonry, though he was not a member of the Masons Company; but as the records are wanting, it is idle to speculate, and absurd to credit to his labors on behalf of our Society what there is not a title of evidence to prove.

Brother Hawkins, an editor of this work, also prepared for the Concise Cyclopedia of freemasonry, the following summary of the arguments on both sides of the question at issue: Those who contend that he was not a Freemason reply as follows:

1. No reference to the convention mentioned by Aubrey has yet been discovered elsewhere, and it remains uncertain whether it ever was held and whether the proposed adoption of the illustrious architect took place or not; also it is inconsistent with the dates given in the 1738 Constitutions.

2. In the Constitutions of 1723, he is only described as lithe ingenious architect,” without any hint of his being a Freemason.

3. It is incredible that Doctor Anderson, when compiling the 1723 Constitutions, should have been ignorant of the details of Wren’s Masonic career which he gave so from in 1735; moreover, he has claimed as Grand Masters are most all distinguished men from Adam downwards, though there was no such office as Grand Master until 1117, and his dates are inconsistent with that given by Aubrey.

4. Subsequent writers all quoted from the 1738 Constitutions and therefore their evidence is worth no more than Doctor Anderson’s, and no such records as Preston refers to can now be found, nor can the legendary history of the candlesticks and the mallet be authenticated. Such are the arguments for and against Wren’s connection with the Craft; those who claim him as a Freemason must reconcile as best they can the conflicting dates given by Aubrey and Anderson: and those who regard his membership as equally a fable with his Grand Mastership must somehow explain away the contemporary evidence of the two newspapers that in the year of his death called him ‘ ‘ that worthy Freemason.”

– Source: Mackey’s Encyclopedia of Freema

sonry

External links:

http://www.freemasons-freemasonry.com/christopher_wren_freemasonry.html

http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/609

http://www.stonehenge-stone-circle.co.uk

http://www.StonehengeTours.com

The only way to get close up to the stones and see 5000 years of grafitti carved onto them is by joing in private access tout. This is where you visit Stonehenge when the site is closed to the public, usually at sunrise or sunset.

If you look very closely at the heel (south west view)stonesits even possible to se a funny carved handshake?

Stonehenge Tour Guide

HisTOURies UK Tours – The Best Tours in Wessex

Read Full Post »

Born in India in October 1900, Jardine was very much a son of empire. He was not an aristocrat but the son of a solicitor and as such perhaps even more conscious of his status as a gentleman and more active in asserting it. Narrowly missing the First World War, he volunteered for the Second despite being past the normal age for active service. Between the wars he fought his own battles on the cricket field. He was aloof, superior, stern and commanding; he was also loyal, fiercely protective of his players and mellowed somewhat with the years, hardly the monster depicted in the Australian press. He left no autobiography and his deeper psychological motivations remain obscure.

Born in India in October 1900, Jardine was very much a son of empire. He was not an aristocrat but the son of a solicitor and as such perhaps even more conscious of his status as a gentleman and more active in asserting it. Narrowly missing the First World War, he volunteered for the Second despite being past the normal age for active service. Between the wars he fought his own battles on the cricket field. He was aloof, superior, stern and commanding; he was also loyal, fiercely protective of his players and mellowed somewhat with the years, hardly the monster depicted in the Australian press. He left no autobiography and his deeper psychological motivations remain obscure.

To carry out their plan, the conspirators got hold of 36 barrels of gunpowder – and stored them in a cellar, just under the House of Lords.

To carry out their plan, the conspirators got hold of 36 barrels of gunpowder – and stored them in a cellar, just under the House of Lords.

the fancy took them. By 1948, the buildings had

the fancy took them. By 1948, the buildings had