Celtic Britain

(The Iron Age) c. 600 BC – 50 AD

Who were they? The Iron Age is the age of the “Celt” in Britain. Over the 500 or so years leading up to the first Roman invasion a Celtic culture established itself throughout the British Isles. Who were these Celts?

For a start, the concept of a “Celtic” people is a modern and somewhat

Celtic Britain was dominated by a number of tribes, each with their own well-defined territory. It is thanks to Roman chroniclers, such as Strabo, Julius Caesar, and Diodorus, that the names of individual tribes are known to us today, albeit in Romanized form.

romantic reinterpretation of history. The “Celts” were warring tribes who certainly wouldn’t have seen themselves as one people at the time.

The “Celts” as we traditionaly regard them exist largely in the magnificence of their art and the words of the Romans who fought them. The trouble with the reports of the Romans is that they were a mix of reportage and political propaganda. It was politically expedient for the Celtic peoples to be coloured as barbarians and the Romans as a great civilizing force. And history written by the winners is always suspect.

Where did they come from? What we do know is that the people we call Celts gradually infiltrated Britain over the course of the centuries between about 500 and 100 B.C. There was probably never an organized Celtic invasion; for one thing the Celts were so fragmented and given to fighting among themselves that the idea of a concerted invasion would have been ludicrous.

The Celts were a group of peoples loosely tied by similar language, religion, and cultural expression. They were not centrally governed, and quite as happy to fight each other as any non-Celt. They were warriors, living for the glories of battle and plunder. They were also the people who brought iron working to the British Isles.

The advent of iron. The use of iron had amazing repercussions. First, it changed trade and fostered local independence. Trade was essential during the Bronze Age, for not every area was naturally endowed with the necessary ores to make bronze. Iron, on the other hand, was relatively cheap and available almost everywhere.

Hill forts. The time of the “Celtic conversion” of Britain saw a huge growth in the number of hill forts throughout the region. These were often small ditch and bank combinations encircling defensible hilltops. Some are small enough that they were of no practical use for more than an individual family, though over time many larger forts were built. The curious thing is that we don’t know if the hill forts were built by the native Britons to defend themselves from the encroaching Celts, or by the Celts as they moved their way into hostile territory.

Usually these forts contained no source of water, so their use as long term settlements is doubtful, though they may have been useful indeed for withstanding a short term siege. Many of the hill forts were built on top of earlier causewayed camps.

Celtic family life. The basic unit of Celtic life was the clan, a sort of extended family. The term “family” is a bit misleading, for by all accounts the Celts practiced a peculiar form of child rearing; they didn’t rear them, they farmed them out. Children were actually raised by foster parents. The foster father was often the brother of the birth-mother. Got it?

Celtic family life. The basic unit of Celtic life was the clan, a sort of extended family. The term “family” is a bit misleading, for by all accounts the Celts practiced a peculiar form of child rearing; they didn’t rear them, they farmed them out. Children were actually raised by foster parents. The foster father was often the brother of the birth-mother. Got it?

Clans were bound together very loosely with other clans into tribes, each of which had its own social structure and customs, and possibly its own local gods.

Housing. The Celts lived in huts of arched timber with walls of wicker and roofs of thatch. The huts were generally gathered in loose hamlets. In several places each tribe had its own coinage system.

Farming. The Celts were farmers when they weren’t fighting. One of the interesting innovations that they brought to Britain was the iron plough. Earlier ploughs had been awkward affairs, basically a stick with a pointed end harnessed behind two oxen. They were suitable only for ploughing the light upland soils. The heavier iron ploughs constituted an agricultural revolution all by themselves, for they made it possible for the first time to cultivate the rich valley and lowland soils. They came with a price, though. It generally required a team of eight oxen to pull the plough, so to avoid the difficulty of turning that large a team, Celtic fields tended to be long and narrow, a pattern that can still be seen in some parts of the country today.

The lot of women. Celtic lands were owned communally, and wealth seems to have been based largely on the size of cattle herd owned. The lot of women was a good deal better than in most societies of that time. They were technically equal to men, owned property, and could choose their own husbands. They could also be war leaders, as Boudicca (Boadicea) later proved.

Language. There was a written Celtic language, but it developed well into Christian times, so for much of Celtic history they relied on oral transmission of culture, primarily through the efforts of bards and poets. These arts were tremendously important to the Celts, and much of what we know of their traditions comes to us today through the old tales and poems that were handed down for generations before eventually being written down.

Druids. Another area where oral traditions were important was in the training of Druids. There has been a lot of nonsense written about Druids, but they were a curious lot; a sort of super-class of priests, political advisors, teachers, healers, and arbitrators. They had their own universities, where traditional knowledge was passed on by rote. They had the right to speak ahead of the king in council, and may have held more authority than the king. They acted as ambassadors in time of war, they composed verse and upheld the law. They were a sort of glue holding together Celtic culture.

Religion. From what we know of the Celts from Roman commentators, who are, remember, witnesses with an axe to grind, they held many of their religious ceremonies in woodland groves and near sacred water, such as wells and springs. The Romans speak of human sacrifice as being a part of Celtic religion. One thing we do know, the Celts revered human heads.

Celtic warriors would cut off the heads of their enemies in battle and display them as trophies. They mounted heads in doorposts and hung them from their belts. This might seem barbaric to us, but to the Celt the seat of spiritual power was the head, so by taking the head of a vanquished foe they were appropriating that power for themselves. It was a kind of bloody religious observance.

The Iron Age is when we first find cemeteries of ordinary people’s burials (in hole-in-the-ground graves) as opposed to the elaborate barrows of the elite few that provide our main records of burials in earlier periods.

The Celts at War. The Celts loved war. If one wasn’t happening they’d be sure to start one. They were scrappers from the word go. They arrayed themselves as fiercely as possible, sometimes charging into battle fully naked, dyed blue from head to toe, and screaming like banshees to terrify their enemies.

They took tremendous pride in their appearance in battle, if we can judge by the elaborately embellished weapons and paraphernalia they used. Golden shields and breastplates shared pride of place with ornamented helmets and trumpets.

The Celts were great users of light chariots in warfare. From this chariot, drawn by two horses, they would throw spears at an enemy before dismounting to have a go with heavy slashing swords. They also had a habit of dragging families and baggage along to their battles, forming a great milling mass of encumbrances, which sometimes cost them a victory, as Queen Boudicca would later discover to her dismay.

As mentioned, they beheaded their opponents in battle and it was considered a sign of prowess and social standing to have a goodly number of heads to display.

The main problem with the Celts was that they couldn’t stop fighting among themselves long enough to put up a unified front. Each tribe was out for itself, and in the long run this cost them control of Britain.

(Note: The terms “England”, “Scotland”, and “Wales” are used purely to indicate geographic location relative to modern boundaries – at this time period, these individual countries did not exist).

Join us on a guided tour of Britain and learn more about the Celts

HisTOURies UK – The Best Tours in British History

Read Full Post »

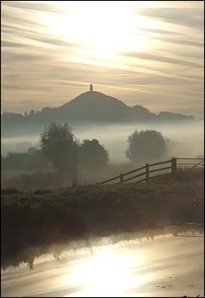

Legends of King Arthur swirl about Glastonbury like a tantalizing fog from the nearby Somerset marshes. The nearby hill fort at South Cadbury has long been suggested as the location for Camelot. Indeed, excavations of South Cadbury suggest that it was in use during the early 6th century, which is the likeliest era for the real Arthur to have lived.

Legends of King Arthur swirl about Glastonbury like a tantalizing fog from the nearby Somerset marshes. The nearby hill fort at South Cadbury has long been suggested as the location for Camelot. Indeed, excavations of South Cadbury suggest that it was in use during the early 6th century, which is the likeliest era for the real Arthur to have lived. Probably not. Legend holds that the earliest church here was founded by St. Joseph of Arimathea in about 60AD, and that when he planted his staff in the earth a thorn tree burst forth.

Probably not. Legend holds that the earliest church here was founded by St. Joseph of Arimathea in about 60AD, and that when he planted his staff in the earth a thorn tree burst forth.