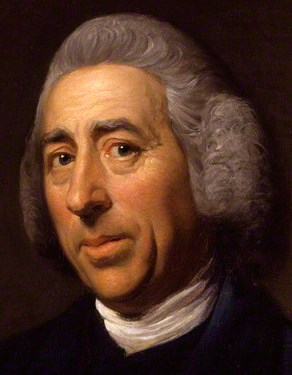

‘Capability’ Brown, best known for designing gardens and landscapes at some of the country’s grandest stately homes including Blenheim Palace, Chatsworth, Highclere Castle, Burghley, Weston Park and Compton Verney.

‘Capability’ Brown’s landscape gardens are synonymous with England’s green and

NPG 6049; Capability Brown

pleasant land with their seemingly natural rolling hills, curving lakes, flowing rivers and majestic trees.

A nationwide festival and programme of events is planned with the opportunity to visit over 150 Brown gardens and landscapes in England, including some not usually open to visitors.

‘Capability’ Brown gardens

After centuries of stiff, formal and enclosed gardens, ‘Capability’ Brown transformed landscapes across England in the 18th century using a new natural style, now considered quintessentially English. He replaced heavy formality with wide open expanses, views and vistas and introduced his signature contouring hills, serpentine lakes and strategically-placed specimen trees.

This was gardening on a vast scale, creating parkland and woodland, and using trees to give the same effect as shrubs in regular gardens.

The Shakespeare of English garden design, his gift was to develop gardens and landscapes that looked natural and in harmony with the surrounding countryside even though they often involved moving thousands of tonnes of earth to create the gentle contours and installing expansive manmade lakes, that looked wonderful but were also part of practical drainage systems.

‘Capability’ Brown

An estate worker’s son, Lancelot Brown was born in August 1716 in the tiny village of Kirkharle, Northumberland.

He mastered the principles of his craft serving as a gardener’s boy at the local country house, Kirkharle Hall. By 1741 he had reached Stowe, an estate in Buckinghamshire where he quickly assumed responsibility for one of the most pioneering and magnificent landscape gardens in England. He stayed at Stowe for ten years and married Bridget Wayet in the local church. While at Stowe, he started to take independent commissions and became hugely sought after by the owners of large country house estates. The 7-mile round grounds at the Burghley estate in Lincolnshire were one of the most important commissions of his career which took more than 25 years to complete. He also practised

architecture and during the 1750s contributed to several country houses including Blenheim, Chatsworth, Harewood and Compton Verney.

Brown earned the nickname of ‘Capability’ as he told his clients that he could see the capabilities for improvement in their gardens and landscapes. He was hardworking, constantly busy and with a habit of not always charging for his work. Reportedly he refused to work in Ireland as he had not yet finished England.

Brown is associated with as many as 260 sites, a large number of which can still be seen today. By the time he died in 1783, 4,000 gardens had been landscaped according to his principles. And his design influence on parks and gardens spread across Northern Europe to Russia and through Thomas Jefferson to the United States.

‘Capability’ Brown Festival

A nationwide festival and events programme is being developed, including the opening of sites not usually accessible to visitors. More details will be released over the coming months.

At 13 major gardens including Blenheim Palace, Chatsworth and Croome, visitors will be able to see speciallycreated ‘Capability’ Brown exhibitions.

For more festival details, an interactive map of ‘Capability’ Brown gardens and landscapes and event listings, visit capabilitybrown.org

For more on England’s gardens, go to visitengland.com

HisTOURies U.K

The Best Tours in British History

http://www.HisTOURies.co.uk

and up to date answer:

and up to date answer: The implication is that layers of paving and sediment were laid over the Period 4 (see table) surface in a fairly swift succession. The subsequent re-pavings were all of rubble and dumped tile. There were also traces of small structures being built against the north wall of the spring reservoir. It seems that what had been built as a great architectural monument in the 2nd or 3rd century was being remodelled much more simply from whatever materials were to hand in the late 4th.

The implication is that layers of paving and sediment were laid over the Period 4 (see table) surface in a fairly swift succession. The subsequent re-pavings were all of rubble and dumped tile. There were also traces of small structures being built against the north wall of the spring reservoir. It seems that what had been built as a great architectural monument in the 2nd or 3rd century was being remodelled much more simply from whatever materials were to hand in the late 4th. The demolition of the temple and baths should be seen in the same light as the construction of refortified hillforts: a community mobilised the resources and labour necessary to remove a major set of structures from the ancient Roman townscape, just as they did to create new high-order settlements in the surrounding countryside. Gildas hints at why they might have done this. Writing in the early 6th century, he rages against British kings for their sins: they were murderers and usurpers. But not once does he call them ‘pagans’.

The demolition of the temple and baths should be seen in the same light as the construction of refortified hillforts: a community mobilised the resources and labour necessary to remove a major set of structures from the ancient Roman townscape, just as they did to create new high-order settlements in the surrounding countryside. Gildas hints at why they might have done this. Writing in the early 6th century, he rages against British kings for their sins: they were murderers and usurpers. But not once does he call them ‘pagans’.

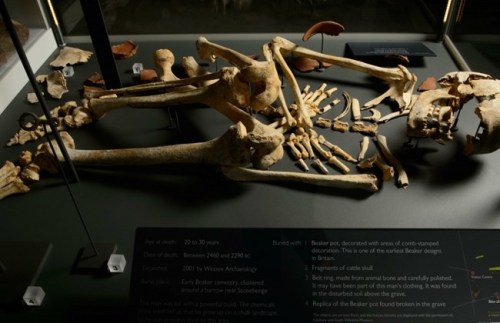

The 51 executed would have been a captured raiding party

The 51 executed would have been a captured raiding party

Osteologist Helen Webb from Oxford Archaeology with one of the skull fragments

Osteologist Helen Webb from Oxford Archaeology with one of the skull fragments